War, disease, division—things aren’t looking too rosy for humanity at the moment. But thanks to Microsoft, at least we’ll be listening to Stevie Wonder after the apocalypse. The tech giant is partnering with Elire Group to etch the world’s music onto glass plates, and bury them in a remote arctic mountainside to ride out the end of the world.

The Global Music Vault will share space with the Global Seed Vault (better known as the Doomsday Vault) in Svalbard, Norway. The Doomsday Vault houses the largest collection of agricultural seeds on the planet. The Global Music Vault aims to match its neighbor seed for song.

Whereas seeds are prepackaged, music is not. So if eternity is the goal, what’s the best medium for the job? Your laptop or smartphone won’t do. Hard drives last about five years before they start to fail; tape is good for no more than 10 years; and CDs and DVDs last 15 years.

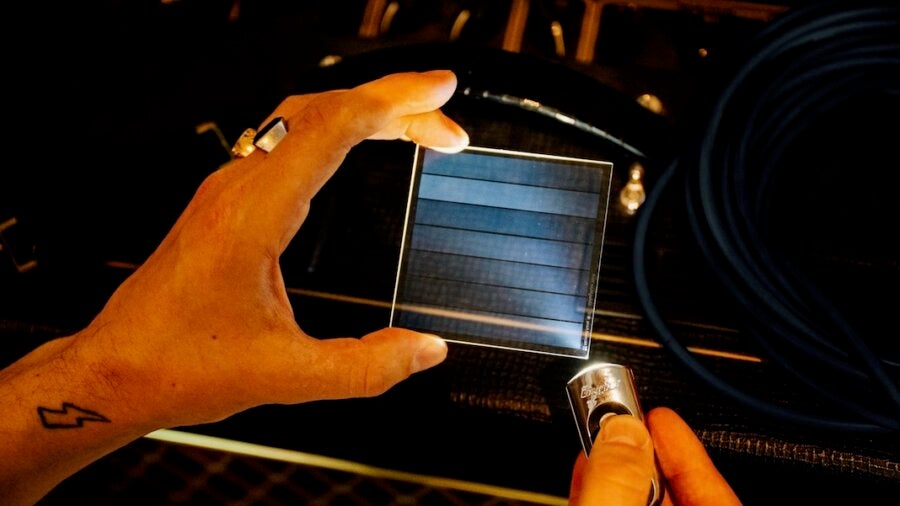

Microsoft was already working on a long-term storage solution—a technology critical for purposes beyond music—known as Project Silica, when they partnered with Elire. The team can encode music with super-fast laser pulses that etch 3D nanoscale patterns into thin three-inch quartz glass wafers. Each wafer holds 100 gigabytes of music, or a little over 2,000 songs. They may soon hold a terabyte and eventually 10 terabytes or more. To retrieve the data, the team shines polarized light through the glass, and a machine learning algorithm translates the patterns it picks up in the glass back into music.

Now, about eternity.

The plates can survive baking, boiling, scouring, flooding, and electromagnetic pulses. (No word on shattering or zombies.) Microsoft estimates the plates, and the data they house, can live up to 10,000 years. “The goal is to be able to store archival and preservation data at cloud scale in glass,” Ant Rowstron, distinguished engineer and deputy lab director at Microsoft Research in Cambridge, told Fast Company.

The Global Music Vault proof-of-concept glass plate, to be deposited in 2023, will include recordings from the International Library of African Music, Kenya’s Ketebul Music archive, and Lebanon’s Fayha Choir. It will also feature Patti Smith and Paul Simon interviews, Manfred Mann and Stevie Wonder concerts, and works by singer-songwriter Beatie Wolfe.

“In an age where music has become increasingly disposable and devalued, this is a wonderful reminder of its long-term value for humanity,” Wolfe told Billboard.

The Global Music Vault isn’t yet committed to using Microsoft’s glass, however. They’ve also experimented with other tech, like high-density QR codes on durable optical film. Future options for archival storage may even include DNA—which Microsoft, among others, is also looking into—because life’s source code offers incredibly high-density storage that can survive thousands of years at low temperatures.

Of course, if the world ends, we may not have the technology—like high-power computing and machine learning—to unlock the vault for a long time. But despite doomsday nicknames for storage libraries like this, it’s not just the end of the world motivating long-term archiving. As we’ve moved information onto digital formats, the limited longevity of those formats—not to mention their decentralized nature, with no librarian to curate and preserve value—is a concern. We’re already losing information, and this trend is sure to accelerate.

Work like Microsoft’s (and others) is crucial if we’re to avoid losing today’s important cultural, legal, philosophical, and scientific contributions. And if some culture-starved pilgrim of the future were to stumble on a mysterious vault lost to time in the permafrost—a cornucopia of seeds and some live Stevie Wonder tracks would be quite the find.

Image Credit: Global Music Vault

* This article was originally published at Singularity Hub

0 Comments