Smartphones are a staple of modern life and are changing how we see the world and show it to others. Almost 90% of Aussies own one, and we spend an average of 5.6 hours using them each day. Smartphones are also responsible for more than 90% of all the photographs made this year.

But compare the camera roll of a 60-year-old with that of a 13-year-old, as we recently did, and you’ll find some surprising differences. In research published in the Journal of Visual Literacy, we looked at how different generations use smartphones for photography as well as broader trends that reveal how these devices change the way we see the world.

Here are five patterns we observed.

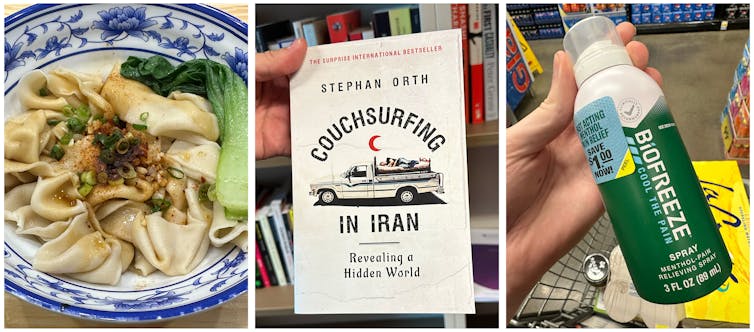

1. We make images more casually and with a wider subject matter

Before the first smartphone camera was released in 2007, cameras were used more selectively and for a narrower range of purposes. You might only see them at events like weddings and graduations, or at tourist hotspots on holidays.

Now, they’re ubiquitous in everyday life. We use smartphones to document our meals, our daily gym progress, and our classwork as well as the more “special” moments in our lives.

Many middle-aged people use smartphones most for work-related purposes. One of our participants put it this way:

I often take photos of info I want to save, or of clients’ work when I want to then email it to myself to put on the computer. I feel like I’ve gotten a little slack on socially taking photos of friends … but in the day-to-day, I feel like I use it very practically now for basically work, grabbing a photo to upload it online somewhere.

2. We aren’t as selfie-obsessed as some would think

Our participants only used their phone’s front “selfie” camera 14% of the time. They acknowledged the stigma around selfies and didn’t want to be perceived as narcissistic.

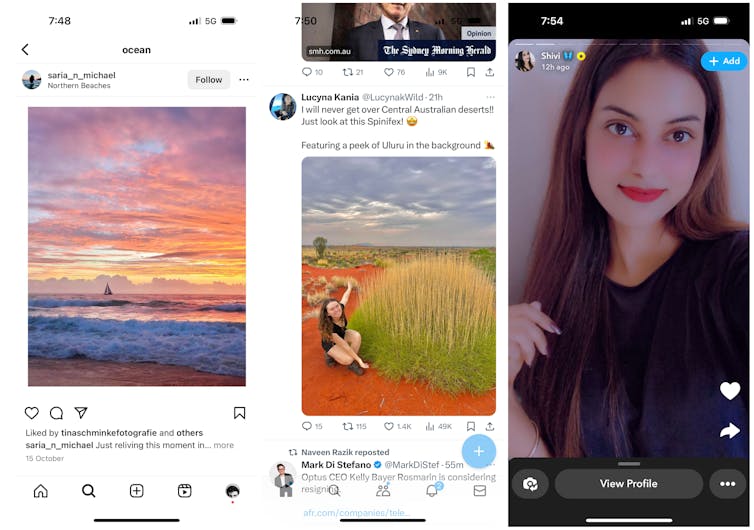

3. We’re seeing more vertical compositions

In years past, whether you had a bulky DSLR camera or a lightweight disposable, the “default” grip was to hold it with two hands in a horizontal way. This leads to photos in landscape orientation.

But the vertical design of smartphones and accompanying apps, such as Instagram and Snapchat, are resulting in more photos in portrait orientation. Participants said holding their smartphone cameras this way was more convenient and faster.

4. We like to keep our distance

Participants made more images of people from farther away compared to getting close. Intimate “head and face” framing was only present in fewer than 10% of the images.

In one participant’s words:

I feel like my friends and I get frustrated with parents, when they’re zooming in a photo or they walk in really close. My mom would always get one like right in my face, like this is too close! I don’t want to see this. The zoom in, oh, it’s frustrating!

5. We get inspired by what we see online

Teenagers in particular mentioned social media, especially Instagram, as influencing their visual sensibilities. Older adults were more likely to attribute their sense of aesthetics to physical media, such as photography books, magazines and posters.

This aesthetic inspiration impacts what we take photos of, and also how we do it. For example, young people mentioned a centred compositional approach most often. In contrast, older generations invoked the “rule of thirds” approach more often.

One participant contrasted generational differences like this:

There seems to be a real lack of interest [by younger people] in say, composition, or the use of light or that sort of aesthetic side of getting an image. When my partner and I were kids […] our access to different aesthetics and images was actually very limited. You had the four channels on TV, you had magazines, you had the occasional film, you had record covers, and that was it, you know. Whereas, kids these days, they’re saturated with images but the aesthetic aspect doesn’t seem to be that important to them.

Why the way we make images matters

While technology is changing the way people see the world and make photographs, it’s important to reflect on why we do what we do, and with what effects.

For example, the camera angle we use might either give or take away symbolic power from the subject. Photographing an athlete or politician from below makes them look more strong and heroic, while photographing a refugee from above can make them look less powerful.

Sometimes the camera angles we use are harmless or driven by practicality – think photographing a receipt to get reimbursed later – but other times, the angles we use matter and can reinforce existing inequalities.

As the number of images made each year increases and new ways to make images emerge, being thoughtful about how we use our cameras or other image-making technology becomes more important.

The research underpinning this article was supported by a research grant from the International Visual Literacy Association. T.J. Thomson receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

The research underpinning this article was supported by a research grant from the International Visual Literacy Association. Shehab Uddin is affiliated with Pathshala South Asian Media Institute. .

* This article was originally published at The Conversation

0 Comments