Many people today worry about how to find time to keep fit and healthy in the midst of their busy lives. Believe it or not, but this was also a problem in ancient times.

So, how did ancient people deal with it?

A universal problem

The physician Galen, who lived from around 129 to 216 AD, dealt with thousands of patients in the city of Rome.

He used to complain some people didn’t devote enough time to keeping fit. In his treatise, Hygiene, Galen wrote one of his patients, a philosopher called Premigenes, was such a workaholic he stayed inside all the time writing books. Because of this bad lifestyle, Premigenes got sick.

Galen said Premigenes needed to work less, and devote more time to getting exercise and some sun.

Some 2,000 years later, most of us will be able to relate to this. The World Health Organization has a number of recommendations for the amount of exercise one should do each week. But it can be difficult to balance work and other commitments with our health and fitness.

The trade-offs of a busy life

People in the Greco-Roman period recognised that being busy has an effect on health.

The writer Lucian of Samosata, from the 2nd century AD, talks in his essay On Salaried Posts in Great Houses about how certain jobs offered workers no time to maintain their health. A bad diet, endless labour and a lack of sleep all contributed to making them unhealthy:

the sleeplessness, the sweating, and the weariness gradually undermine you, giving rise to consumption, pneumonia, indigestion, or that noble complaint, the gout. You stick it out, however, and often you ought to be in bed, but this is not permitted. They think illness a pretext, and a way of shirking your duties. The general consequences are that you are always pale and look as if you were going to die any minute.

The doctors of the time also noticed this problem. Galen said, in his opinion, one of the determinants of whether we are able to be healthy or not is the amount of free time we have.

He recognised some people had no choice but to be “bound up with the circumstances of their activities” – such as those taken into slavery – but noted others seemed to have

chosen a life caught up in the circumstances of their activities, either through ambition or whatever kind of desire, so they are least able to spend time on the care of their bodies.

Galen was also affected by this problem. As a doctor he had little free time, and his normal routine was often interrupted by patients’ problems. Nonetheless, he explains how, in his 20s, he started adhering to a daily health routine:

after I reached the age of 28, having persuaded myself that there is an art of hygiene, I followed its precepts for the whole of my subsequent life, and was never sick with any disease apart from the occasional ephemeral fever in some degree.

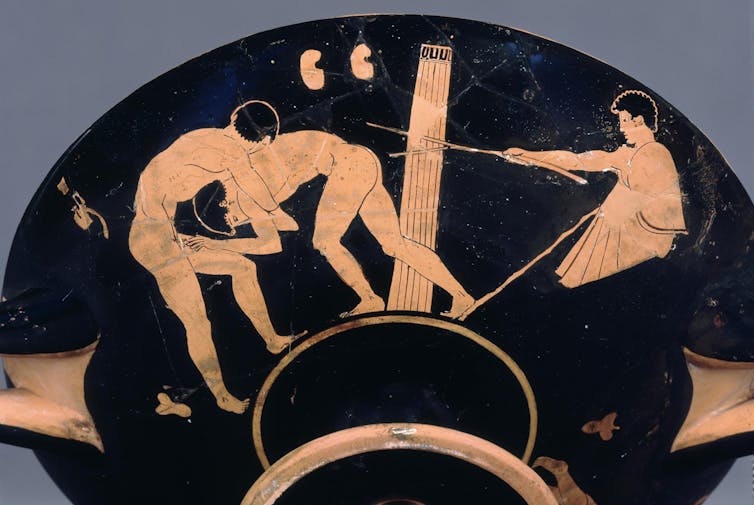

This routine involved eating one full meal each evening, and doing some sort of exercise every day. One of these exercises may have been wrestling, as he also mentions dislocating his shoulder while wrestling at the gym at the age of 35.

One advantage of Galen’s routine was its flexibility. He just had to find some time each day to eat a meal and move his body.

He said many other doctors of his time didn’t keep healthy. They overworked, ate and drank too much, and didn’t exercise enough.

Galen wasn’t saying everyone should take up his routine, however. He noted everyone has a different nature, and people should take up routines that best suit their bodies.

How the ancients kept fit

One wealthy Athenian citizen named Ischomachus, who lived in the 5th century BC, used to keep fit by exercising on his daily commute.

When he had to go into the city, he would run or walk, or alternate between the two. He’d do the same when visiting his farm. Even the famous philosopher Socrates praised Ischomachus for keeping healthy in this efficient way, in spite of always being busy with commitments.

Galen recommended all people should play ball games involving running and throwing to keep fit. Ball games, he thought, were a good option because they exercised the whole body and didn’t require much money or equipment.

For his overweight patients, he would recommend a routine of fast running and a slimming diet – one meal a day, comprised of foods that would fill the patient, but which were “poorly nourishing”.

One doctor from the 7th century AD, Paul of Aegina, also identified how some people let their busy schedules get in the way of their health.

He describes the sort of person who used to have a healthy routine, but no longer follows it due to being busy:

He who spends his time in business ought to consider whether, in the former period of life, he had been in the habit of taking exercise, or whether, though not taking exercise, he bears that habit well, and escapes from diseases by having free perspiration.

Paul recommended busy people lighten their commitments and resume as much of their old routine as possible. If they can’t exercise as they did before, then at least they could eat healthily, he said. The worst thing would be to abandon both healthy eating and exercise.

Developing healthy habits

The philosopher Aristotle said health is partly a matter of personal responsibility. If someone lives an unhealthy lifestyle and doesn’t follow the advice of doctors, it’s no surprise, Aristotle thought, if he or she ends up unhealthy.

Generally speaking, the ancients seem to have believed it is up to each person to find flexible habits that can help them stay fit. And while this can be difficult, they thought it was imperative to a life well-lived – much as we do today.

It seems some things about being human don’t change.

Konstantine Panegyres does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

* This article was originally published at The Conversation

0 Comments