An immune tag-team promises to hold the virus in check for years—even without medication.

HIV was once a death sentence. Thanks to antiretroviral therapy, it’s now a chronic disease. But the daily treatment is for life. Without the drug, the virus rapidly rebounds.

Scientists have long hunted for a more permanent solution. One option they’ve explored is a stem cell transplant using donor cells from people who are naturally resistant to the virus. A handful of patients have been “cured” this way, in that they could go off antiretroviral therapy without a resurgence in the virus for years. But the therapy is difficult, costly, and hardly scalable.

Other methods are in the works. These include using the gene editor CRISPR to damage HIV’s genetic material in cells and mRNA vaccines that hunt down a range of mutated HIV viruses. While promising, they’re still early in development.

A small group of people may hold the key to a simpler, long-lasting treatment. In experimental trials of a therapy called broadly neutralizing anti-HIV antibodies, or bNAbs, some people with HIV were able to contain the virus for months to years even after they stopped taking drugs. But not everyone did.

Two studies this month reveal why: Combining a special type of immune T cell with immunotherapy “supercharges” the body’s ability to hunt down and destroy cells harboring HIV. These cellular reservoirs normally escape the immune system.

One trial led by the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) merged T cell activation and bNAb treatment. In 7 of 10 participants, viral levels remained low for months after they stopped taking antiretroviral drugs.

Another study analyzed blood samples from 12 participants receiving bNAbs and compared those who were functionally cured to those who still relied on antiretroviral therapy. They zeroed in on an immune reaction bolstering long-term remission with the same T cells at its center.

“I do believe we are finally making real progress towards developing a therapy that may allow people to live a healthy life without the need of life-long medications,” said study author Steven Deeks in a press release.

A Long and Winding Road

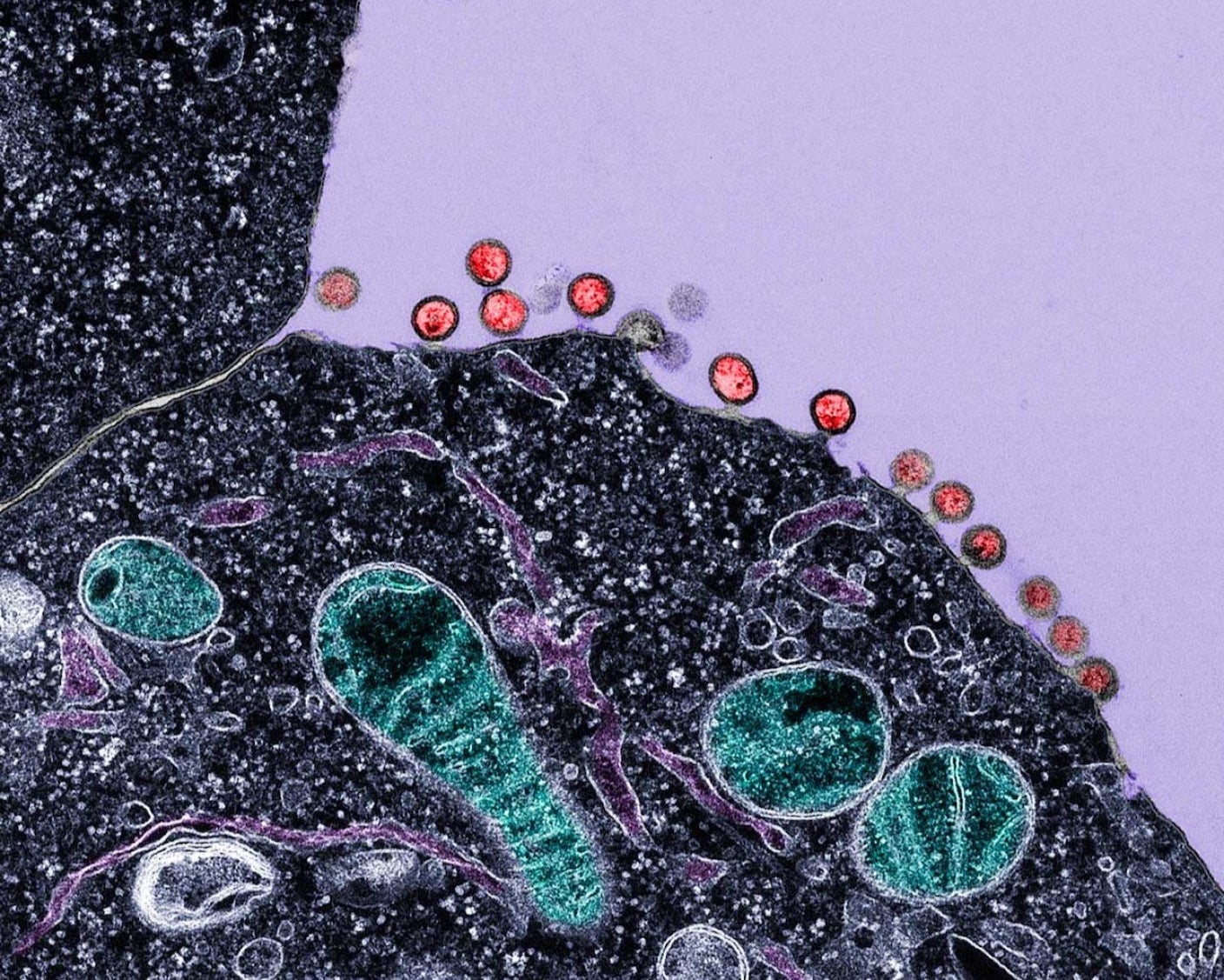

HIV is a frustrating foe. The virus rapidly mutates, making it difficult to target with a vaccine. It also forms silent reservoirs inside cells. This means that while viral counts circulating in the blood may seem low, the virus rapidly rebounds if a patient ends treatment. Finally, HIV infects and kneecaps immune cells, especially those that hunt it down.

According to the World Health Organization, roughly 41 million people live with the virus globally, and over a million acquire the infection each year. Preventative measures such as a daily PrEP pill, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, guard people who don’t have the virus but are at high risk of infection. More recently, a newer, injectable PrEP formulation fully protected HIV-negative women from acquiring the virus in low- to middle-income countries.

Once infected, however, options are few. Antiretroviral therapy is the standard of care. But “lifelong ART is accompanied by numerous challenges, such as social stigma and fatigue associated with the need to take pills daily,” wrote Jonathan Li at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who was not involved in either study.

Curing HIV once seemed impossible. But in 2009, Timothy Ray Brown, also known as the Berlin patient, galvanized the field. He received a full blood-stem-cell transplant for leukemia, but the treatment also fought off his HIV infection, keeping the virus undetectable without drugs. Other successes soon followed, mostly using donor cells from people genetically immune to the virus. Earlier this month, researchers said a man receiving a non-HIV-resistant stem cell transplant had remained virus-free for over six years after stopping antiretroviral therapy.

While these cases prove that HIV can be controlled—or even eradicated—by the body, stem cell transplants are hardly scalable. Instead, the new studies turned to an emerging immunotherapy employing broadly neutralizing anti-HIV antibodies (bNAbs).

From Theory to Trial

Compared to normal antibodies, bNAbs are extremely rare and powerful. They can neutralize a wide range of HIV strains. Clinical trials using bNAbs in people with HIV have found that some groups maintained low viral levels long after the antibodies left their system.

To understand why, one study examined blood samples from 12 people across four clinical trials. Each participant had received bNAbs treatment and subsequently ended antiretroviral therapy. Comparing those who controlled their HIV infection to those who didn’t, researchers found that a specific type of T cell was a major contributor to long-term remission.

Remarkably, even before receiving the antibody therapy, people with less HIV in their systems had higher levels of these T cells circulating in their bodies. Although the virus attacks immune cells, this population was especially resilient to HIV and almost resembled stem cells. They rapidly expanded and flooded the body with healthy HIV-hunting T cells. Adding bNAbs boosted the number of these T cells and their killer efficiency destroying HIV safe harbor cells too. Without a host, the virus can’t replicate or spread and withers away.

“Control [of viral load] wasn’t uniquely linked to the development of new types of [immune] responses; it was the quality of existing CD8+ T cell responses that appeared to make the difference,” said study author David Collins at Mass General Brigham in a press release.

If these T cells are key to long-term viral control, what if we artificially activated them?

A small clinical trial at UCSF tested the theory in 10 people with HIV. The participants first received a previously validated vaccine that boosts HIV-hunting T cell activity. This was followed by a drug that activates overall immune responses and then two long-lasting bNAb treatments. The patients were then taken off antiretroviral therapy.

After the one-time treatment, seven participants maintained low levels of the virus over the following months. One had undetectable circulating virus for more than a year and a half. Like Collins’s results, bloodwork found the strongest marker for viral control was a high level of those stem cell-like T cells. People with rapidly expanding levels of these T cells, which then transformed into “killer” versions targeting HIV-infected cells, better controlled the infection.

“It’s like…[the cells] were hanging out waiting for their target, kind of like a cat getting ready to pounce on a mouse,” said study author Rachel Rutishauser in a press release.

Findings from both studies converge on a similar message: Long-term HIV management without antiretroviral therapy depends, at least in part, on a synergy between T cells and immunotherapy. Methods amping up stem cell-like T cells before administering bNAbs could give the immune system a head start in the HIV battle and achieve longer-lasting effects.

But these T cells are likely only part of the picture. Other immune molecules, such as a patient’s naturally occurring antibodies against the virus, may also play a role. Going forward, the combination treatment will need to be simplified and tested on a larger population. For now, antiretroviral remains the best treatment option.

“This is not the end game,” said study author Michael Peluso at UCSF. “But it proves we can push progress on a challenge we often frame as unsolvable.”

The post New Immune Treatment May Suppress HIV—No Daily Pills Required appeared first on SingularityHub.

* This article was originally published at Singularity Hub

0 Comments